I tend to get a bit self-conscious about showing off the digital stuff I make during conference presentations. Mostly because when I do show something I’m doing it not to show off the digital tool, but to make an illustrative point about the larger topic of my paper. Yet because the digital whatever is something new and different it tends to overshadow the more substantive points about literature, history, and culture I’m trying to make. I also get self-conscious because I’m very aware that most of what I do is done on a shoestring budget, comparatively, entirely alone. This differs it from a lot of grant funded projects that tend to have slicker interfaces and a lot more energy behind them. I don’t say that as an excuse—just as a realization of my limitations.

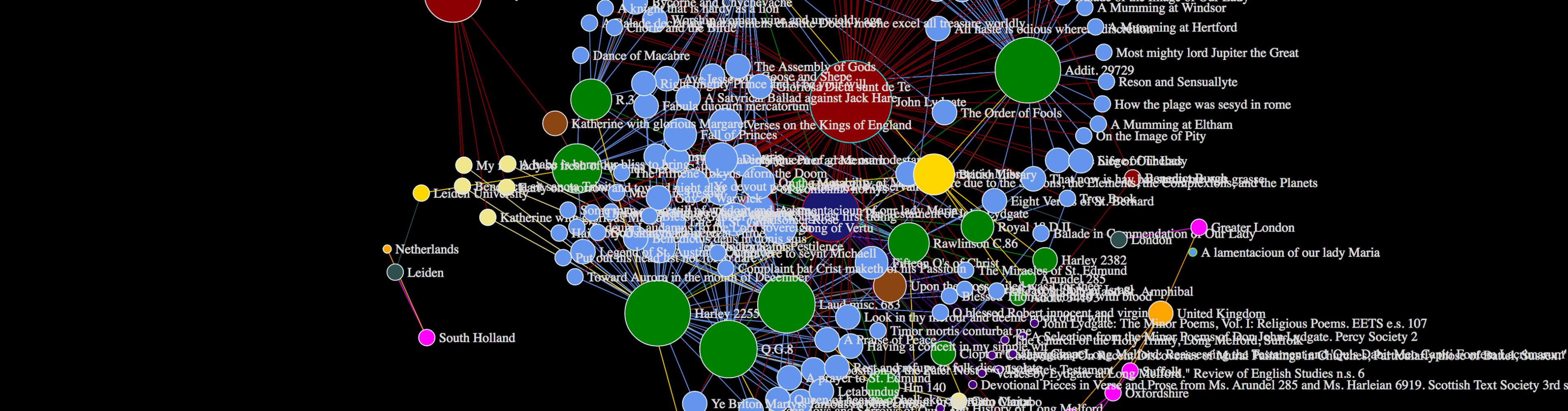

That said, during the question and answer period I’ve often been asked how I did things like the 3d model I created for the Clopton chantry chapel or the force-directed graph of the Lydgate corpus. While I’ve explained the reasoning behind each project in answer to conference questions I have not really articulated the full process of how I went from the physical object to the perceived need to the digital representation. Nor have I explained in any serious manner what tools I used. Since this site is, in part, intended to show greater transparency my intention is to change that through a series of posts beginning first with the 3d model and then transitioning to the force-directed graph. Along the way I also intend to mention ways that someone might do some of the steps I mention that could be cost-prohibitive a little cheaper and the pros and cons of doing so.

The Problem

I talk about how unique the various aspects of Lydgate’s Testament at Long Melford are much more extensively in “Lydgate at Long Melford,” but the basic problem of a facsimile of the stanzas at the chantry chapel from a technical standpoint is one of presentation: because the various stanzas of the poem are laid out around the roofline of the chapel it is a physical impossibility to sit still and read the poem in its entirety. It has to be read by, at the very least, turning around and more likely by moving throughout the space and reading each of the panels in turn.

The standard way of presenting a facsimile online is by displaying a series of pictures laid out as though they were the pages of a book. You can see it in several digital versions of medieval texts:

- Digital Mappa

- The Digital Vercelli Book

- The Electronic Beowulf

- The Piers Plowman Electronic Archive

- The Siege of Jerusalem Electronic Archive

And it is entirely possible to lay out the stanzas at Long Melford in this manner. In fact, I do so in the Minor Works of John Lydgate site. In this case, though, laying them out as though they were manuscript pages in a codex removes the realization that the way the panels have to be read functions differently in the chapel space. Moreover, much like how the tendency to subdivide codices into particular texts for online display eliminates the sense of the poem in relation to the other items in the codex, displaying the Testament at Long Melford as a series of flat images in sequences eliminates the ability to understand the poem in the space as it was intended by the artists and artisans that produced it. To recapture that relationship to the non-textual elements—the architectural paratext—I decided early on that I needed to develop a three dimensional model of the space.

Methodology

I knew I’d be doing this work essentially as an independent researcher as I'm a postdoc and my ability to get institutional funding is largely limited due to budgetary constraints. Furthermore, I knew that what I really wanted to do is give a viewer the ability to view the panels containing the stanzas as they were laid out at Long Melford rather than create a fully accurate, immersive model of the space, for reasons I've articulated elsewhere. Due to the cost issue a specialized tool like a LIDAR scanner was outside of my budget. Moreover, the type of system I was likely to be able to afford tends to work best close up to the object of study, which works much better with objects like statues rather than full spaces like rooms. The LIDAR tool I was able to afford—a Structure Sensor coupled with a commodity tablet and the Skanect 3D imaging software package—proved inadequate for a full room scan.

Another option is to take careful measurements of the room and then build the model using the Sketchup 3d modeling tool, which at its face seemed like it would be ideal to build out the space. Applying textures in a meaningful manner to the model, however, was an exercise in frustration and the more I played with attempting to build complex objects the more I realized it would take much more time than I had with an incomplete payoff. Therefore, the method that worked best for my purposes was stereophotogrammetry.

Stereophotogrammetry, at its heart, is the study of recovering the exact positions of surface points in a series of photographs in a three-dimensional space. If you imagine a ray of light coming out from the camera (or from your eye, as was commonly thought in medieval conceptions of optics theory) and striking the object of your study, then each time you take a picture from a different position the ray intersects the object differently. Take enough pictures, and you can develop a fairly accurate three-dimensional model of the object or the space you want to work with.

Materials

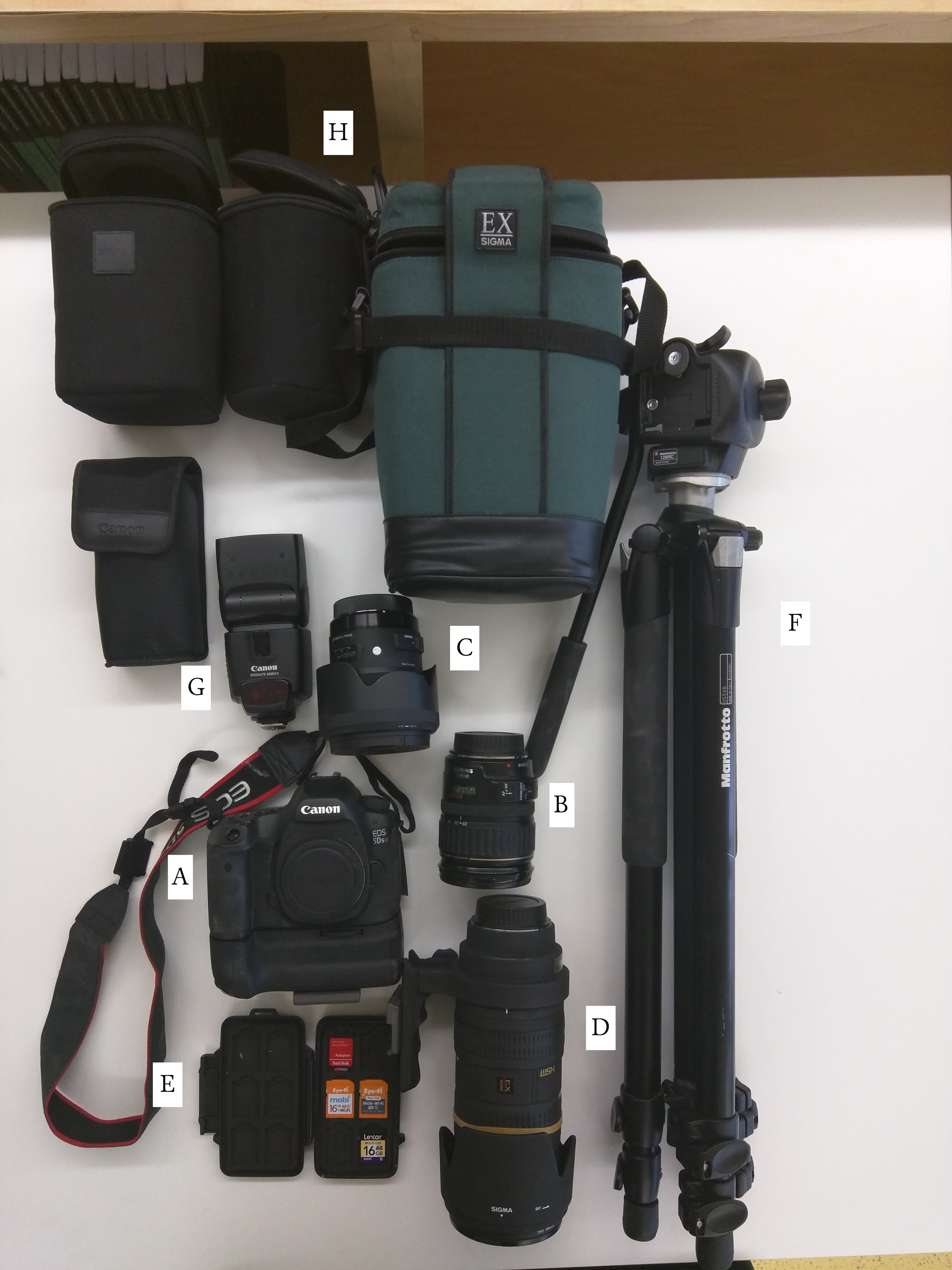

The benefit of Stereophotogrammetry is that it can be done using commodity hardware—which means that the same camera that you use to take pictures on a trip can also be used to develop models to display the spaces you were in. In my case I also have an interest in developing a library of images of architectural features in parish churches, cathedrals, and other areas in East Anglia for research purposes. Many of these features are high up in cathedral naves so I had invested in a decent telephoto lens and an DSLR. This meant that when the time came I already had a fairly decent photo setup:

Since I was shooting near the 500mm range of the largest of these lenses extensively while taking the pictures of the roof bosses of Norwich Cathedral, I also had a tripod capable of holding the camera and this large lens steady. Quality optics allowed me to take fairly clear pictures, limited mostly by my talent or lack thereof with the camera. This was very important when I was taking the pictures that came to be on the Minor Works of Lydgate site as well as the pictures I use to help illustrate my articles, as they served both as solid references to allow me to remember aspects of the poems that would have taken more time to note than I had in situ. You do not need all of this to do work with stereophotogrammetry, however.

Since all we're really doing in building up a model is using stereophotogrammetry to compare points in multiple photographs, pictures from your phone or a consumer-grade point and shoot will work, albeit not at the same resolutions or possibly with the same clarity. The most important thing, rather than the type of camera you select, is the technique.

Technique

To take stereophotogrammetric pictures of a space, you need to hold the camera steady and parallel to ground level. A tripod will help you out with this significantly.

One of the best practices for stereophotogrammetry if you are using a camera that has interchangeable lenses is to use a prime, or fixed focal length lens. A zoom lens is generally a compromise in clarity across its entire focal range, while a prime lens will generally show sharper images as long as the image is properly framed. If you are using a point and shoot camera or a zoom lens, then it is best to keep it at a consistent focal level. With the point and shoot I took the image with in the third slide above I simply turned the camera on and did not attempt to zoom the lens in on the opposite wall at all. Likewise, with the 50-500 mm lens I left it at the 50mm focal point. The important thing here is consistency.

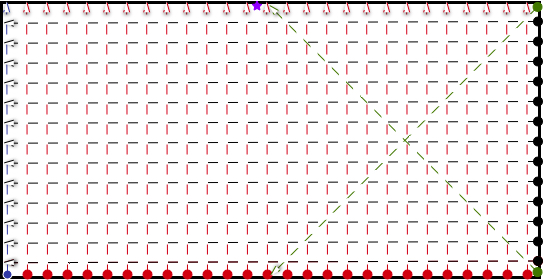

In order to capture the room, place the tripod against one of the walls with the camera facing perpendicular to it, as shown in the first set of images above. In most rooms, this means that the camera will also be perpendicular to the opposite wall. After you've done so you take a picture then move a set distance either to the left or right and repeat the process again, moving around the room while doing so. I use the length between the tripod legs as a handy guide to help me keep the distance consistent by setting my foot next to the rightmost foot of the tripod, for example, then lifting the tripod and moving it to the right and setting what had been the leftmost foot where the rightmost foot was.

I generally make three passes around the room: one with the tripod's legs fully extended but the central column fully depressed, one with both the legs and the central column fully extended, and one with the legs and central column fully extended and the camera pointing at the joint between the roof and wall on the opposite side of the room. A final run down the center of the room with the camera set perpendicular to the floor in order to capture the roof completes the sequence. As you can imagine from the number of dots in the diagram above this will easily result in dozens or even hundreds of pictures taken during a single session. The saving grace is that you are not interested in capturing anything "interesting" as you do this, so you can concentrate on making sure the camera is focused properly after each move throughout the room. It is a good idea to start with anything in particular you want to capture just to be on the safe side.

Tips and Tricks

By and large, using the method mentioned in the section above will get you usable results. In taking pictures of architectural features and inscriptions, however, I have run into some issues that I had to either get creative about overcoming or come up with a solution to after the fact. Since "after the fact" generally means when I return home from the trip I'd like to pass them along to save you similar problems.

Always shoot raw

This is sort of a truism of any sort of serious photography in general, but if you can you should always be taking your pictures in the camera's raw format. What this means is that the file saved is exactly what the image sensor of the camera captured, rather than a compressed version as you might expect with .jpg or other lossy formats. If you shoot raw, you'll have the ability to do a number of things in post-production to improve your images, and you can always put them in those lossy formats to be uploaded online after the fact. The biggest thing you'll want to do, especially if you've been taking lots of pictures over an extended period, is try to reduce the amount of "noise," or digital distortion of the image, that occurs as you shoot and the image sensor heats up. There are techniques to mitigate this (mostly by having a decent sensor and giving it time to cool down between shots) but I guarantee at some point you'll be trying to get as much done in as short a period as possible and noise will creep in. Luckily this can be corrected in post-production. Most of my images are put through the PhotoNinja postproduction suite and then stored in .tiff format, which I'll explain a bit more about in a future post. While not perfect, this has largely worked for my purposes.

Get a heavier tripod than you think you'll need

I cannot stress enough that a solid base from which to take your images will improve their clarity immensely, especially if you're trying to take pictures at extreme distances. Although it's not likely you'll be doing that if you're trying to take photos for sterophotogrammetry, the solid base will still make it much less likely that any vibrations will upset your shot.

It's tempting to go with a lighter tripod, especially if you're using a point and shoot camera. They take up much less space than the full-size tripod, are less of a pain to lug around, and in perfect conditions can provide similar shots. They are also much flimsier in construction, usually don't extend out as far, and as the final slide in the sequence below shows generally lack the ability to position the camera properly. You get what you pay for—if you are going to do any sort of serious research photography that is more than taking quick reference pictures in an archive purchase a decent tripod.

Make sure you have enough storage and battery power

Most of us use SD or CF cards in the multi-gigabyte range to store pictures, and so it can feel like enough space to last forever. That said, it's better to shoot in the highest resolution you can and reduce it in post-production, and those higher resolutions mean larger image files. Even if an individual picture is only 12MB (which is on the low end—some of my raw files are 60MB per image) that means that you are only getting about eighty-five pictures per gigabyte of storage. It's not likely you're going to fill up the card completely in a single day's shooting, but it's entirely conceivable that you'll run out of storage before the trip is over unless you bring extras. This issue can be further exacerbated if you convert those raw files into both .tiff and .jpg files—a .tiff of the 60MB raw file I mentioned above is about 150MB. Unless you're much better about having plenty of storage space on your computer than I am you'll need some sort of external storage to keep everything together. I bring a 5TB external hard drive with me when I'm traveling, copy all the images to it after each day's session, and then set those files to backup to offsite storage in the background using the internet provided by where I'm staying. You may find, however, that bandwidth is capped in your location or that the amount of time it would take to store all of the files is more than the time you'll be staying. If this is the case, be sure to back up that external drive the minute you arrive back from your trip or when you have a better internet connection. I also try to keep the images on the cards until I absolutely have to recover the space as an extra added backup.

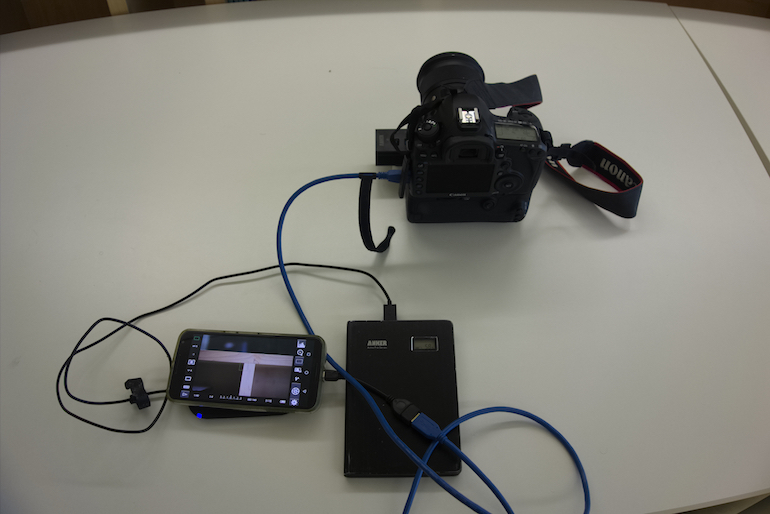

Another option is to shoot directly to a disk drive rather than to a CF or SD card. This can seem tempting, but if you choose to do so you'll need to make sure you have a a way to power your disk drive as the camera will not provide enough energy to keep the drive "live." This can be done by buying an external USB battery and either a powered USB hub or a y-cable, then plugging either the hub or the "extra" usb connection into the battery. What exact setup works best for you will depend largely on the type of camera you're using and whether you need to keep the camera connected to anything else via USB. Also note that a powered USB hub will likely not be able to transfer data from your camera to multiple devices, as most cameras don't have the ability to communicate as both a host and a device at the same time. This can be overcome by purchasing a USB On-the-go (or OTG) cable, which allows devices to serve as hosts in a USB connection if necessary.

In my case, I carry a number of SD and CF cards with me, as shown in the picture of my equipment above, and also carry two external batteries to help reduce the drain on the dedicated batteries for the camera. My camera is also equipped with a battery grip, which allows me to keep two batteries (or a battery and an AC adapter) in the camera at all times. When I use the AC adapter, I have a cable running from the AC adapter to the external battery or to a wall socket, depending on the circumstance. Another nice benefit of the particular battery grip I have is that it allows you to load the camera with four AA batteries if needed, so I have been known to carry a pack in order to really follow a "belt and suspenders" approach.

As you can imagine by the length of this particular tip, storage and battery issues are the primary problem I think you'll run into on the fly. Anything else either has to be accepted as it cannot be dealt with on-site, or can be planned for prior to the trip. My general rule is overkill—if you have more storage and power than you think you'll need you will probably find you have a little more than enough. If you plan for having enough, as I did when I took pictures of the Norwich Cathedral roof bosses, you'll have to end your photo taking early each day to allow your camera batteries to recharge.

Shoot Live View if it's an option

While it is not as important for shooting stereophotogrammetric pictures I still believe that you should shoot with live preview or live view if it is an option on your camera. It is for most cameras with LCD's on the back. The larger screen real estate will let you see any issues with camera focus, objects blocking the lens, or odd camera settings in a way that the viewfinder may not. Furthermore, when combined with a remote--even one as simple as a shutter release cord--it can allow you to see take the picture without any worry about vibrations distorting the image.

The one issue with both live view and the more traditional viewfinder is that you cannot see it if the camera is tilted up at an angle. This is a problem when you want to take pictures of ceilings, as I did in the Clopton chapel and in my Norwich Cathedral images. One solution is to buy a small compact mirror and use it to reflect what the screen is showing. I used this at Norwich to good effect, but it is very cumbersome to hold the mirror in one hand, the shutter remote in the other, and stay out of the way of people trying to navigate the space around you. A simpler method, if you have an Android-based cellphone or tablet and the USB On-the-go cable I mentioned above, is to download the DSLR Controller application. This application allows the phone's screen to serve as a live view screen, which means you can forego both mirror and remote cable. Note, however, that you are in essence limiting yourself to the battery life of your cellphone with the screen continually on if you go this route, as most cellphones only have one cable connection for data and charging. If your phone is capable of wireless charging using the Qi standard you can connect the charging pad to an external battery and charge the phone while using it as a viewscreen, however.

Conclusion

While useful to improve both your efficiency and the variety of images you can take, none of the wireless chargers, extra batteries, or plethora of lenses and storage devices are necessary to take stereophotogrammetric images, or even to engage in research photography in general. They just make it a bit easier. As I stressed above, all you really need is a steady hand and a camera, so if this interests you you might try taking some shots of a room on your next research trip. In the next digital post, I'll talk about what to do with those pictures once you've taken them -- postprocessing using the Photo Ninja suite I mentioned above as well as how you convert the images to a three-dimensional model using software.

Add new comment